It makes you wonder what's on the minds of the legislators in the other 4 states, like the old Trident ads that claimed "4 out 5 dentists recommend sugarless gum"--what the hell is that fifth dentist thinking? But I digress.

Compliance is a problem, however. The ad campaign implores: "It can wait." That's meant to keep us from peeking at the screen when we hear that ping.

This account seems especially plausible in light of the data showing that talking on a hands-free cell phone is just has distracting as talking on a hand-held device (Horrey & Wickens, 2006). The overt activity (holding the phone, checking the message) may be less important than the unobservable mental activity. A recent study offered support for this hypothesis, examining the consequences to attention of refraining from checking a message or call.

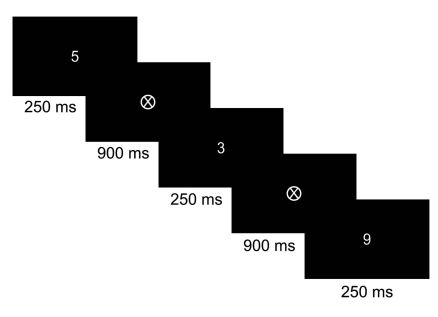

Cary Stothart and colleagues asked subjects to perform a simple, but attention-demanding lab task. A digit appeared every 900 ms, and subjects were to press a button as quickly as possible when it did...except if the digit was a 3.

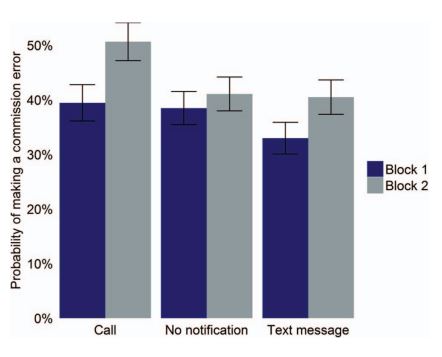

There were three conditions. Some subjects received four text messages on their phone during the second block of trials, some received phone calls, and the third group served as a control.

A unique and clever feature of the study is that subjects were unaware of its purpose. They were asked for their cell phone number along with other information as part of the study; the program controlling the attention task contained a script that executed the calls or texts. The program also assigned subjects to condition randomly, so the experimenter did not know in advance which condition the subject would be in.

An experimenter remained in the room, seated behind the subject, to monitor whether the subject actually checked his or her phone, and to monitor whether the phone was off or silenced. (Each was seldom the case.)

The data showed, as expected, that unanswered calls and text notifications led to performance decrements. One measure is the probability of pressing the button when a 3 appears, shown below.

Another way to measure attention in this task is the frequency of very fast response times. If a subject doesn't really evaluate the digit, he or she can fall into a rhythm of pushing the button more or less in sync with the appearance of the digit, because its timing is predictable. The frequency of this sort of response increased in block 2 for the call and the text conditions.

The authors did not include a condition that would really help support their interpretation. They ought to have people perform this task in pairs. If my cell phone rings it ought to distract me, but have little impact on you, because you won't wonder who is trying to make contact.

How detrimental this distraction effect would be to driving is hard to say; obviously some driving conditions (a straight, empty interstate) are less demanding than others (Boston rush-hour in a snowstorm). Still, the impact on overall accident rates is predictable. Even a small distraction effect, multiplied by the number of driving hours in this and other countries where smartphones are the norm, means more accidents.

If we really want people to refrain from texting while driving, "turn it off," is better advice than "it can wait."

I doubt, however, that even well-intentioned drivers will remember to do so. The solution would be greater use of existing apps that block texting while driving.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed