Let’s start with the new science. Douglas Sperry and colleagues sought to replicate Hart & Risley, who reported the 30 million word gap—that’s the projected difference in total number of words directed to a child by caregivers when comparing children of parents on public assistance and children of parents in professional positions. Sperry and his team claim not to find a statistically reliable difference among parents of different social classes.

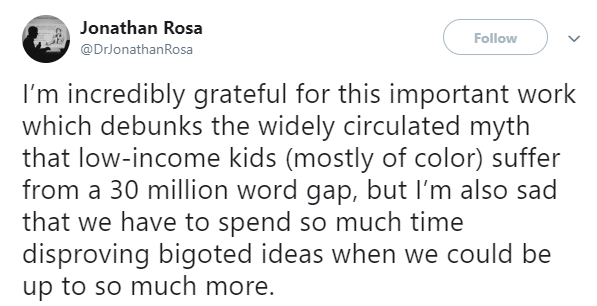

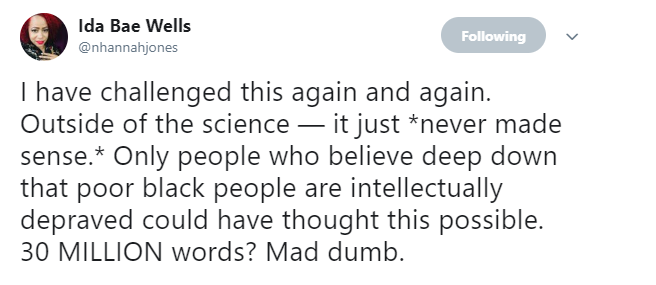

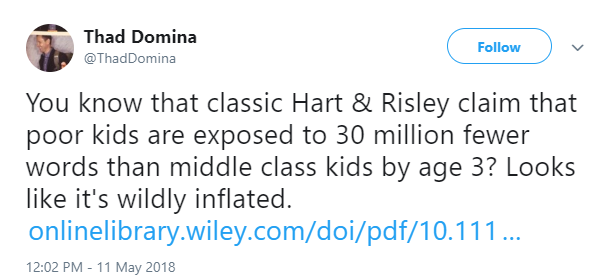

Twitter was quick to pounce:

But the Sperry report doesn’t really upend Hart & Risley.

First, Sperry et al. claim that the Hart & Risley finding has never been replicated. I am not sure what Sperry et al. mean by “replicate,” because the conceptual idea that socioeconomic status and volume of caregiver→child speech has been replicated. (The following list is not offered as complete—I stopped looking after I found five.)

Gilkerson et al (2017)

Hoff (2003)

Hoff-Ginsberg (1998)

Huttenlocher et al (2010)

Rowe (2008)

None of these is an exact replication---they have variations in methods, population, and analyses. The same is true of Sperry et al, and funnily enough that study has a fairly significant difference—they didn't include a group of professional parents which is key if your main concern is the size of the gap between professional and public assistance parents.

It’s also worth noting that Sperry et al speculated that their results may be more representative of how parents actually talk, because the researchers used an unobtrusive recording system. Hart and Risley (and most other researchers) had a researcher observing parents and children, so perhaps parents in different SES groups reacted differently in the presence of researcher, the guess being that poor people might clam up, or the wealthier might show off by talking more. I'll leave alone the assumptions underlying that speculation, but I will point out that, first, I doubt observer effects would count for much because the observations occurred over the course of years; people get used to being observed. Second, Gilkerson et al (2017) used the same unobtrusive system that Sperry did and observed the association of SES and caregiver speech.

Another odd thing about the Sperry et al paper is their emphasis on bystander speech (i.e., speech that is not directed to the child but happens in the child’s presence.) This is odd because multiple studies indicate that child *can* learn from such speech, but more often learn little or nothing (e.g., here and here).

Sperry points out that in some cultures children are seldom addressed directly, yet learn to talk. But maybe children in those cultures learn “if someone’s talking, I should listen, even if it’s not addressed to me because they may say something that’s important to me.” In most households in the US, if you’re not being addressed it’s less likely that the speech is important to you, so the child likely does not redirect attention from whatever he or she was doing to the speech.

So all in all, I don’t think this failure to replicate overturns Hart & Risley, coming as it does in the face of several successful replications. As to whether the gap is 30 million or some other figure…I don’t know, maybe somebody thought the absolute value mattered. I doubt any psychologists did. We would care about the predictive power of the caregiver speech. On the whole, there’s still pretty good reason to think there’s an association between SES and child-directed speech from parents. (For more on this issue, see the recent blog by Roberta Golinkoff and her colleagues.)

BUT thinking that there’s pretty good evidence for the association is not AT ALL the same as thinking it ought to influence policy. There are two issues here.

First, do we understand this phenomenon well enough to intervene? Second, should we?

In answer to “do we understand enough?” I’d say “no.” The volume of words is the variable you hear about most, but it may not be the most important. It may be the conversational back and forth that matters. Or the diversity of speech. Or the gestures that go with speech. And oral language is only one contributor to vocabulary size and syntactic complexity. Maybe we should intervene to get more parents reading to their children, or better, using dialogic reading strategies. At the very least, I’d like to see a small-scale intervention study (not just a correlational study) showing positive results of asking caregivers to talk their children more, before I would be ready to draw a strong conclusion that volume of caregiver talk is causal to children’s language capabilities.

The second question—if we were pretty sure we knew that a factor is causal, should we intervene?—is much more fraught. As I have considered at length elsewhere, questions like this are outside of the realm of science. You’re contemplating using science, but whether or not to intervene is not a scientific question. It’s a question of values. You are seeking to change the world. That brings costs and the promise of benefits. Will it be worth it? It depends on what you value.

That’s what people on Twitter were responding to on this issue (some explicitly, some implicitly)—the assumption that parents in poverty ought to parent more like middle-class parents. Then their kids would be successful…according to middle class values. That conclusion entails the obvious corollary that parents can eliminate any disadvantage their child has, so if they don’t, well, it’s no one’s fault but their own.

I agree with this argument to a point. The prospect of using science to tell people how to parent makes me very uneasy.

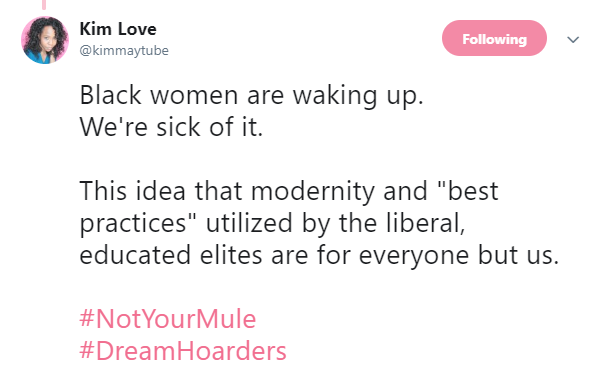

On the other hand, should we fiercely defend parenting practices in the name of cultural equality or because we don’t want to let powerful institutions off the hook if we know those practices put children at a disadvantage in school, and later, in the job market? (Reminder, I don’t think that such evidence currently exists on parental speech volume.) Wealthy parents keep pace with what researchers suggest will help children flourish, and then defend the right of parents living in poverty to use parenting practices that put poor children at a disadvantage? In a long series of tweets (in which she raises many of the criticisms of the Sperry et al study that I raised above) Twitter user @kimmaytube closed with this pointed comment

People who are concerned about the impact of proposed applications of science will have on low-income communities and individuals raise valid points, which they sometimes undercut with rash claims about the invalidity of the scientific studies.

I’ve seen this repeatedly on the subject of grit and self-control. Again, there are very legitimate questions to ask about the values that underlie the assumption that we should make kids more self-controlled and/or more gritty, and questions about the costs to children and institutions should we try to intervene that way. These are separate issues than questions about the scientific standing of grit and self-control as explanatory constructs.

Twitter notwithstanding, I encourage you to bear the distinction in mind.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed