Last week, the results of the 2011 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) were published. This test compared reading ability in 4th grade children.

U.S. fourth-graders ranked 6th among 45 participating countries. Even better, US kids scored significantly better than the last time the test was administered in 2006.

There's a small but decisive factor that is often forgotten in these discussions: differences in orthography across languages.

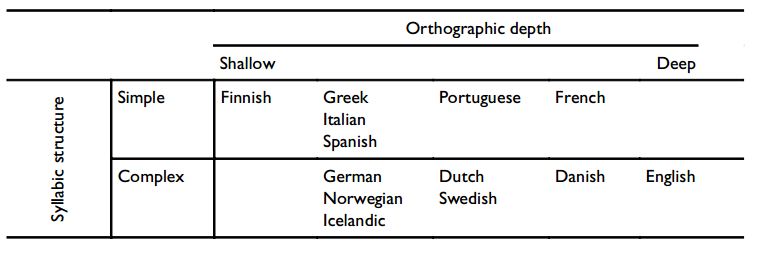

In some languages the correspondence is relatively straightforward, meaning that a given letter or combination of letters reliably corresponds to a given sound. Such languages are said to have a shallow orthography. Examples include Finnish, Italian, and Spanish.

In other languages, the correspondence is less consistent. English is one such language. Consider the letter sequence "ough." How should that be pronounced? It depends on whether it's part of the word "cough," "through," "although," or "plough." In these languages, there are more multi-letter sound units, more context-depenent rules and more out and out quirks.

Another factor is syllabic structure. Syllables in languages with simple structures typically (or exclusively) have the form CV (i.e., a consonant, then a vowel as in "ba") or VC (as in "ab.") Slightly more complex forms include CVC ("bat") and CCV ("pla"). As the number of permissible combinations of vowels and consonants that may form a single syllable increases, so does the complexity. In English, it's not uncommon to see forms like CCCVCC (.e.g., "splint.")

Here's a figure (Seymour et al., 2003) showing the relative orthographic depth of 13 languages, as well as the complexity of their syllabic structure.

This highlights two points, in my mind.

First, when people trumpet the fact that Finland doesn't begin reading instruction until age 7 we should bear in mind that the task confronting Finnish children is easier than that confronting English-speaking children. The late start might be just fine for Finnish children; it's not obvious it would work well for English-speakers.

Of course, a shallow orthography doesn't guarantee excellent reading performance, at least as measured by the PIRLS. Children in Greece, Italy, and Spain had mediocre scores, on average. Good instruction is obviously still important.

But good instruction is more difficult in languages with deep orthography, and that's the second point. The conclusion from the PIRLS should not just be "Early elementary teachers in the US are doing a good job with reading." It should be "Early elementary teachers in the US are doing a good job with reading despite teaching reading in a language that is difficult to learn."

References

Seymour, P. H. K., Aro, M., & Erskine, J. M. (2003). Foundation literacy acquisition in European orthographies. British Journal of Psychology, 94, 143-174.

Wolf, M., Pfeil, C., Lotz, R., & Biddle, K. (1994). Towarsd a more universal understanding of the developmental dyslexias: The contribution of orthographic factors. In Berninger, V. W. (Ed), The varieties of orthographic knowledge, 1: Theoretical and developmental issues.Neuropsychology and cognition, Vol. 8., (pp. 137-171). New York, NY, US: Kluwer

RSS Feed

RSS Feed