Educators have sought to improve inferencing. In some cases they can teach students reading comprehension strategies: create a summary, for example, or create a graphic organizer. The task provides some structure that will prompt the student to make the necessary inferences. Alternatively, students might be taught more directly to make inferences, usually by instruction to elaborate on what they read in the text, to use cues in the text that provide clues to inferencing (e.g., words like “because,” or “so,”), and to monitor their comprehension.

A new meta-analysis of inference instruction (Elleman, 2017) shows that it’s quite effective, but carries some important caveats…ones that I’ve mentioned before.

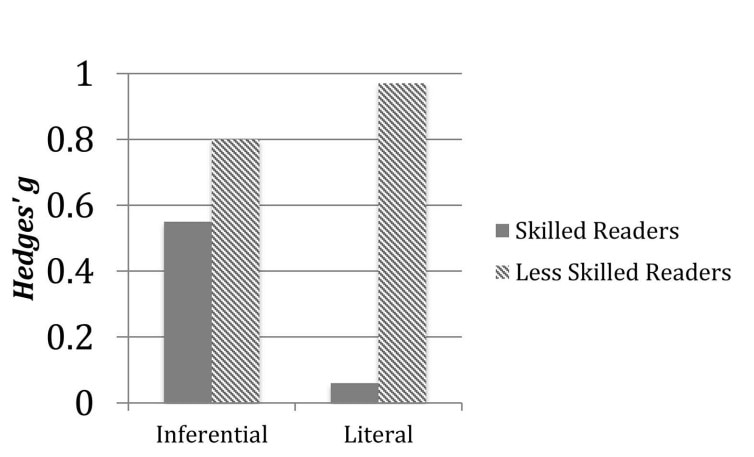

The overall mean effect size on comprehension of inference instruction was a healthy g = .58. Elleman also evaluated separately comprehension due to inferences, and literal comprehension, and observed a difference moderated by ability.

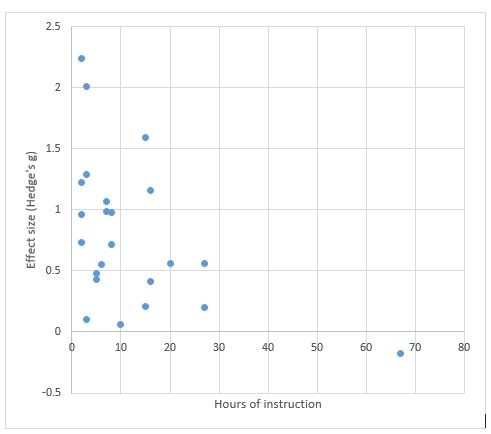

Still more interesting to me was the report that the amount of instructional time had no impact on the effectiveness of the intervention, which I’ve shown in the graph below, compiled from a data table in the paper.

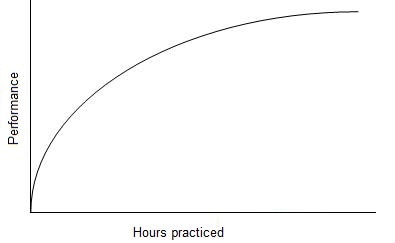

This finding is important because it provides an important clue to the mechanism by which this instruction helps. Practice usually helps, especially early in training. The curve looks like this

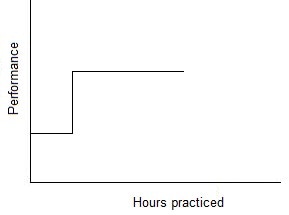

This failure to observe a practice effect is more understandable if the relationship of practice and performance for inference generation look more like this:

As Elleman notes, theories of reading have centered on the knowledge from long-term memory needed to make inferences (Kintsch, 1998) and/or the working memory capacity needed to hold information in mind simultaneously so meanings can be compared (Daneman & Carpenter, 1980). Neither of these is going to change over the course of 10 hours of instruction.

And that’s the practical implication of this meta-analysis. There’s a big benefit to inference instruction, but all of the benefit accrues rapidly. There seems to be no point in spending extended classroom time on the practice.

Similar results have been observed in meta-analyses of studies examining the impact of reading comprehension strategy instruction. Gail Lovette and I (2014) reported on nine meta-analyses of typically developing readers and of readers either identified with a reading disability, or at risk. In each case, the pattern was the same: a large effect with few hours of instruction, and no benefit to more instruction. (This piece was published as a commentary in Teachers College Record and seems to have disappeared from the website. Email me if you’d like a copy.)

This interpretation is also consistent with theories of reading comprehension. Inferences are situation specific: you can’t really teach how to make inferences because the inference to be made depends on the content of the text. Rather, you can teach them to seek and use some cues (probably a causal connection here) and you can teach them that it’s important to make inferences. But making them requires broad background knowledge in long term memory.

That is an essential goal to improve reading comprehension, but it is a goal requiring years of planning, not hours.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed