The researchers (Sadler et al., 2013) tested 181 7th and 8th grade science teachers for their knowledge of physical science in fall, mid-year, and years end. They also tested their students (about 9,500) with the exact same instrument.

Each was a twenty-item multiple choice test. For 12 of the items, the wrong answers tapped a common misconception that previous research showed middle-schoolers often hold. For example, one common misconception is that burning produces no invisible gases. This question tapped that idea:

What makes this study interesting is that it tests teacher subject-matter knowledge directly (instead of using a proxy like courses taken, or degrees) and that it directly measures one aspect of pedagogical content knowledge, namely, student misconceptions. The dependent measure of interest is student gain scores in content knowledge over the course of the year.

The results?

Teachers content knowledge was good, but not perfect. They got about 84% of the questions right.

Their knowledge of student misconceptions was not as good. Teachers correctly identified just 43% of those. (And their students had, as in previous studies, selected those incorrect items in high numbers.)

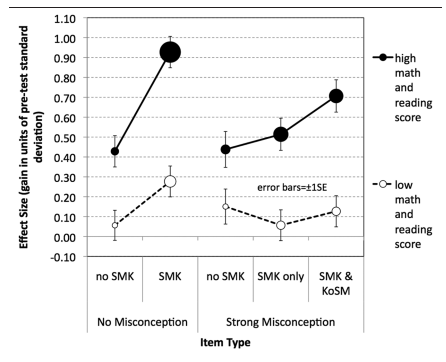

And what type of teacher knowledge matters to student learning? It turns out to interact with past student achievement, as measured by standard math and reading tests.

Look first at learning for concepts without a common misconception. If teachers have subject matter knowledge (SMK in the graph) students learn the concept better. In fact, low-achieving students learned nothing about a concept if teachers didn't know the concept themselves. High-achieving students did. The researchers speculate they may have learned the content from a textbook or other source.

For the strong misconception items, the low-achieving students learned very little, whatever the teacher knowledge. For high-achieving students, knowledge mattered, and they were most likely to learn when their teacher had both subject-matter knowledge and knew the misconceptions their students likely held (KoSM in the graph).

So the overall message is not that surprising. Students learn more when their teachers know the content, and when they can anticipate student misconceptions.

Somewhat more surprising (and saddening), low-achieving students are especially vulnerable when teachers lack knowledge. High-achieving students are more resilient.

There are limitations to this study, the most notable being that the sample is far from random (teachers were volunteers), and that the test was zero-stakes for all.

The strength was the direct measure of both types of knowledge, and that the researchers could examine the relationship of knowledge to performance at the level of individual items. One hopes we'll see more studies using this type of design.

Reference:

Sadler, P. M., Sonnert, G., Coyle, H.P., Cook-Smith, N., & Miller, J.L. (2013) Student learning in middle school science classrooms. American Educational Research Journal, 50, 1020-1049.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed