I know this is convoluted and honestly I don't think it matters much, but I'm trying to provide some context. Here's what I really wanted to get at.

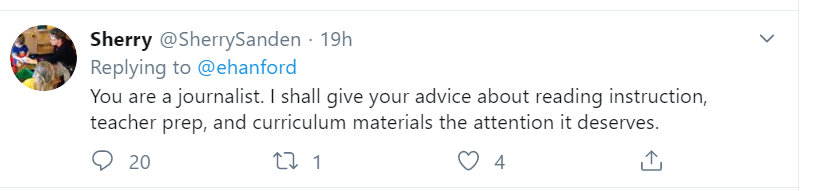

This is one of Sanden’s tweets in reply to Hanford.

I’d like to comment on the obvious implication that Sanden should be taken more seriously because of her job; she’s a professor of education at Illinois State. She has credentials: she has a PhD in the relevant discipline, she publishes research on the topic, presents at professional conferences, and so on.

This is called argument from authority. In this instance, here’s the form Sanden is hoping it will take.

Proposition 1: Sanden has research-based reasons for believing that X is true about early literacy.

Proposition 2: Random tweeters don’t understand research very well, but have good reason to believe Proposition 1 is true (because of Sanden’s credentials).

Conclusion: Random tweeters believe that conclusion X is supported by research.

I considered argument from authority at more length in When Can You Trust the Experts, but here’s a short version.

Believing something because someone else believes it rather than demanding and evaluating evidence makes you sound either lazy or gullible. But we yield to the authority of others all the time. When I see my doctor I don’t ask for evidence that the treatments he prescribes are effective, and when an architect designed a new deck for my house I didn’t ask for proof that it could support the weight of my grill and outdoor furniture. I believed what they told me because of their authority.

I think education researchers don’t speak with that kind of authority and (apparently unlike Sanden) I don’t think we deserve it. I can point to two key differences between a doctor (or architect, or accountant, or electrician, etc) and education researchers.

First, I yield authority to someone who has been vetted by a credible entity. I know that, unless you break the law, you cannot practice medicine (or follow the other professions named) without being licensed by the state of Virginia. I haven’t looked into the matter, but I have no reason to think that the accrediting agencies aren’t doing an acceptable job. For one thing, most of the professionals I hire achieve what I expect them to achieve.

Education researchers, in contrast, are not licensed by a credible authority.

Anyone can take the title “education researcher.” That’s why we must point to earmarks of authority like academic degrees, training, and publications ; these make the silent claim “people with expertise think I’m an expert too,” which is, of course, a bit circular. Sometimes researchers mention television, radio and public speaking appearances. That’s called “social proof,” boiling down to “other people think I’m worth listening to.

The problem is that these earmarks of authority are not very reliable. The marketplace is cluttered with purveyors of snake oil who bear degrees, and even some who have published articles in “peer-reviewed” journals. As readers of this blog know, the idea that “peer review” is a guarantee of high quality in a journal does not bear close scrutiny.

But there’s a second, more important difference between education research and professions where people readily accept argument from authority. Those other fields have more accepted truths.

When I get an electrician to figure out why the breaker in my living room keeps flipping, I understand she may be more or less skillful in diagnosis and repair than another licensed electrician. What I don’t expect is that she could have wildly different—perhaps completely opposing—ideas about how electricity works and how to wire a house compared to someone else I might have called.

Education researchers do not speak with one voice, and that makes it hard to expect an argument from authority will work, as they take this form:

Proposition 1: Sanden says that when it comes to early reading, scientific research suggests “X” is true.

Proposition 2: Willingham says that when it comes to early reading, scientific research suggests “not X” is true.

Proposition 3: Random tweeter has equally good reason to believe (based on their credentials) that Proposition 1 and Proposition 2 are true.

Conclusion: ??????

We can’t make arguments from authority if equally authoritative people disagree.

Part of the problem is that people who enter these arguments actually come at the problems with different assumptions and understandings about what constitutes evidence, and indeed, what it means to know something. That’s most obvious when we have had very different training. Cognitive psychologists and researchers in critical theory address aspects of education that are largely non-overlapping, and you’ll find some of each

these folks in most schools of education, with similar credentials.

I’ve argued elsewhere that those of us in education research would do ourselves a favor if we would make our assumptions more explicit, as well as the limitations of the tools in our analytic toolbox—what problems are our methods well suited to answer and what can’t we answer? I think you don’t hear that often enough.

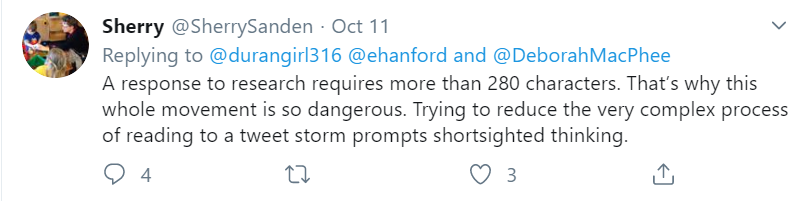

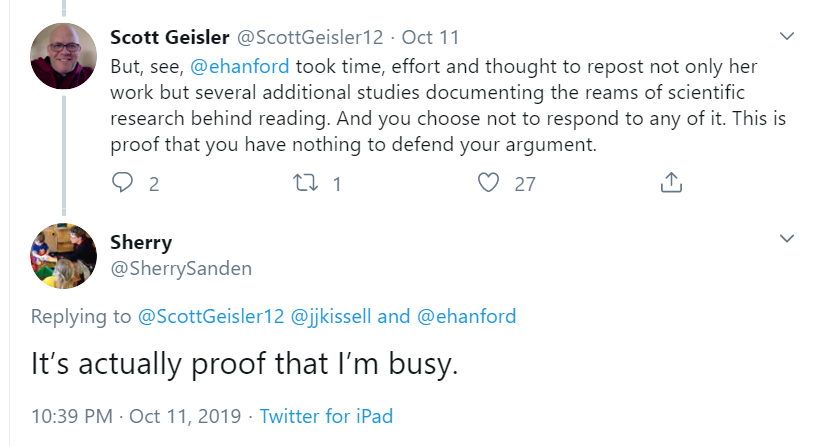

A final note. Later in the thread Sanden posted this

RSS Feed

RSS Feed