You do end feeling as though you have a richer impression of the person than that gleaned from the stark facts on a resume. But there's no evidence that interviews prompt better decisions (e.g., Huffcutt & Arthur, 1994).

A new study (Dana, Dawes, & Peterson, 2013) gives us some understanding of why.

The information on a resume is limited but mostly valuable: it reliably predicts future job performance. The information in an interview is abundant--too abundant actually. Some of it will have to be ignored. So the question is whether people ignore irrelevant information and pick out the useful. The hypothesis that they don't is called dilution. The useful information is diluted by noise.

Dana and colleagues also examined a second possible mechanism. Given people's general propensity for sense-making, they thought that interviewers might have a tendency to try to weave all information into a coherent story, rather than to discard what was quirky or incoherent.

Three experiments supported both hypothesized mechanisms.

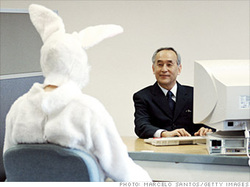

The general method was this. 76 students at Carnegie Mellon University served as interviewers. They were shown the academic record of a fellow student who they would then interview. (The same five students served as interviewees throughout the experiment.)

The interviewers were to try to gain information through the interview to help them predict the grade point average of the interviewee in the next semester. The actual GPA was available so the dependent measure in the experiment was the accuracy of interviewers' predictions.

The interviewers were constrained to asking yes-or-no questions. The interviewee either answered accurately or randomly. (There was an algorithm to produce random "yeses" or "nos" on the fly.) Would interviewers do a better job with valid information than random information?

It's possible that limiting the interview to yes or no questions made the interview artificial so a third condition without that constraint was added, for comparison. This was called the natural condition.

The results? There was evidence for both dilution and for sense-making.

Dilution because interviewers were worse at predicting GPA than they would have been if they had used previous GPA alone. So the added information from the interview diluted the useful statistical information.

Sense-making because ratings made after the interview showed that interviewers generally agreed with the statement "From the interview, I got information that was valuable in making a GPA prediction."

There were no differences among the accurate, random, and natural conditions on these measures.

It's possible that the effect is due, at least in part, to the fact that interviewers themselves pose the questions. That makes them feel that answers confirm their theories about the interviewee.

So in a second experiment researchers had subjects watch a video of one the interviews conducted for the first experiment, and use that as the basis of their GPA prediction. All of the results replicated.

Keep in mind, what's new in this experiment is not the finding that unstructured interviews are not valid. That's been long known. What's new is some evidence as to the mechanisms: dilution and sense-making.

And sense-making in particular gives us insight into why my colleagues in the psychology department have never taken Tim Wilson's suggestion seriously.

Reference:

Dana, J., Dawes, R., & Peterson, N. (2013) Belief in the unstructured interview: The persistence of an illusion. Judgement and Decision Making, 8, 512-520.

Huffcutt, A. I. & Arthur, W. Jr. (1994). Hunter and Hunter (1984) revisited: Interview validity for entry-level jobs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 184-190.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed