When you think of a college class, what image comes to mind? Probably a professor droning about economics, or biology, or something, in an auditorium with several hundred students. If you focus on the students in your mind’s eye, you’re probably imagining them looking bored and, if you’ve been in a college lecture hall recently, your image would include students shopping online and chatting with friends via social media while the oblivious professor lectures on. What could improve the learning and engagement of these students? According to a recent literature review, the results of which were reported by Science, Wired, PBS, and others, damn near anything.

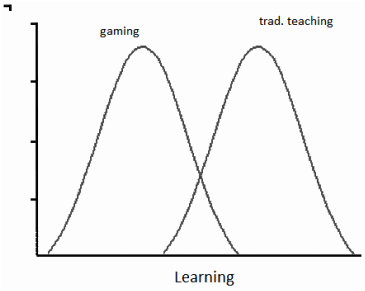

Scott Freeman and his associates (Freeman et al, 2014) conducted a meta-analysis of 225 studies of college instruction that compared “traditional lecturing” vs. “active learning” in STEM courses. (STEM is an acronym for science, technology, engineering, and math.) Student performance on exams increased by about half a standard deviation. Students in the traditional lecture classes were 1.5 times as likely to fail as students in the active learning classes.

Previous studies of college course interventions have been criticized on methodological grounds. For example, classes would experience either traditional lecture or active learning, but no effort would be made to evaluate whether the students were equivalently prepared when they started the class. Freeman et al. categorized the studies in their meta-analysis by methodological rigor, and reported that the size of the benefit was not different among studies of high or low quality.

That’s encouraging. What’s surprising is the breadth of the activities covered by the term “active learning” and how little we know about their differential effectiveness and why they work. According to the article, active learning “included approaches as diverse as occasional group problem-solving, worksheets or tutorials completed during class, use of personal response systems with or without peer instruction, and studio or workshop course designs.” The authors do not report on differential effectiveness of these methods.

In other words, in most of the studies summarized in the meta-analysis professors were still doing a whole lot of lecturing, but every now and then they would do something else. The “something else” ostensibly made students think about the course material, digest it in some way, generate a response. The authors certainly believe that that’s the source of the improvement, citing Piaget and Vygotsky as learning theorists who “challenge the traditional, instructor-focused, ‘teaching by telling’ approach.”

I’m ready to believe that that aspect of the activity was important (although not because of theory advanced by Piaget and Vygotsky nearly a century ago.) But It would have been useful to evaluate the impact of an active control group-- that is, where active learning is compared to a class in which the professor is asked to do something new, but does not entail active learning (e.g., ask the professor to show more videos). That’s important because interventions typically prompt a change for the better. John Hattie estimates that interventions boost student learning by 0.3 standard deviations, on average.

The exact figures are not reported, but it appears that for most studies the lecture condition was business-as-usual, the thing that typically happens. An active control is important to guard against the possibility that students improve because the professor is energized by doing something different, or holds higher expectations for students because she expects the “something different” to prompt improvement. It’s also possible that asking the professor to make a change in her teaching actually improves her lectures because she reorganizes them to incorporate the change.

It may seem captious to harp on the “why.” To be clear, I think that focusing on making students mentally active while they learn is a wonderful idea, and an equally wonderful idea is giving instructors rules of thumb and classroom techniques that make it likely that students will think. But knowing the source of the improvement will allow individual instructors to tailor methods to their own teaching, rather than following instructions without knowing why they help. It will also help the field collectively move to greater improvement.

Perhaps the best news is that the effectiveness of college instruction is on people’s minds. This past winter I visited a prominent research university, and an old friend told me “I’ve been here twenty-five years, and I don’t think I heard undergraduate teaching mentioned more than twice. In the last two years, that’s all anybody talks about, all over campus.”

Amen.

References

Freeman, S, Eddy, S. L, McDonough, M., Smith, M. K, Okoroafor, N. Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Hattie, J. (2013). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed