The latest example comes from a recent paper reporting a randomized control trial of adaptive vs. static practice in Dutch schools.

It seems self-evident that adaptive practice will be superior to static. In static practice, each student receives the same set of practice materials of graded difficulty: easy, medium, hard, with difficulty defined by the performance of a large cohort of students. In the adaptive algorithm, the proportion of questions correctly answered is factored into the probability of seeing a particular type of question: if a student is getting all of the easy questions right, what’s the point of posing more? Why not move on to more challenging content?

Adaptive practice is one of the reasons offered that personalized learning ought to lead to greater achievement.

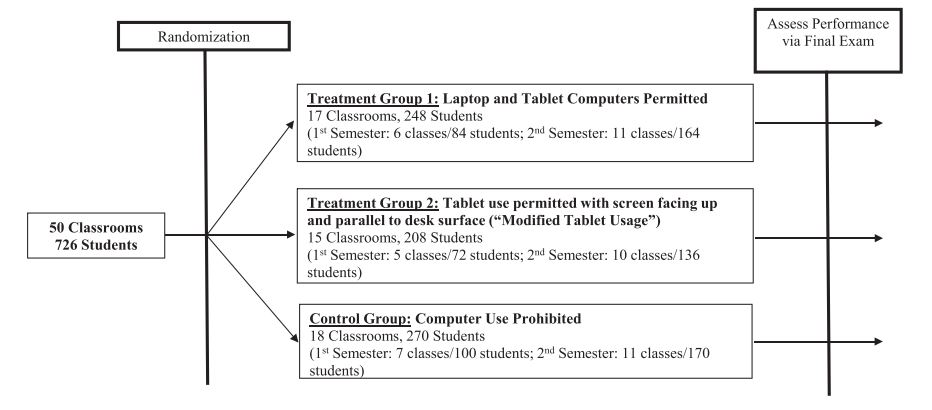

The experiment tested 1,051 Dutch 7th-9th graders studying either Dutch, Biology, History, or Economics over the course of one academic year. Assignment to static or adaptive practice was assigned by classroom, and students were blind to condition. All students received the same instruction (a hybrid of a digital environment and traditional paper textbook) and all homework was the same. The independent variable was implemented only through extra practice; students were asked to practice at least 15 minutes per week, but any more practice than that was taken at their own initiative.

We might expect that, because students are practicing at their own initiative, they will use the adaptive program less, given that the problems will likely be more difficult. The proportion of students who used the practice module did not differ between conditions, hovering around 90% in both cases. Students in the adaptive condition did indeed work more difficult problems and they also practiced a little bit longer per session…but they worked fewer problems than students in the static condition. Presumably, more difficult problems required more time per problem.

Nevertheless, they showed no advantage on a summative test. In fact, better prepared students (those who had passed the summative test before the experiment began) were slightly negatively impacted by the adaptive regimen compared to the static. (There was no effect for students who had failed the last summative test.)

Post-experimental interviews showed that students did not know whether their practice had been adaptive or static, and showed no difference in students’ attitudes towards the practice.

Why was there not a positive effect of adaptive testing?

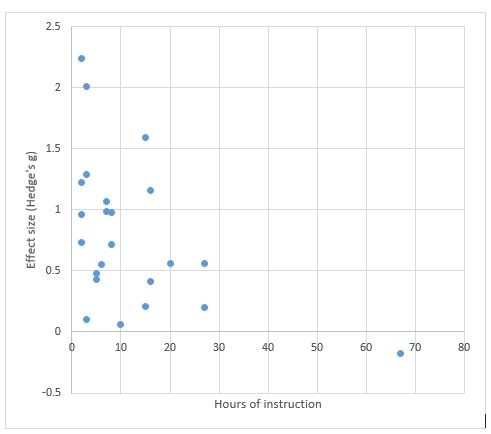

One possibility is low dosage. The intervention was only 15 minutes per week and although students could have practiced more, few did. At the same time, the intervention lasted an entire school year, the N was fairly large, and an effect was observed (in the unexpected direction) for the better prepared students.

Another possibility is that the program was effective in getting challenging problems to students, but ineffective in providing instruction. Students in the adaptive condition saw more difficult problems, but they got a lot of them wrong. Perhaps they needed more support and instruction at that point, so the potential benefit of stretching their knowledge and skills was not realized.

Another possibility is that the adaptive group would have shown a benefit on a different outcome measure. As the authors note, the summative test was more like the static practice than the adapative practice. Perhaps the adapative group would have shown a benefit in their readiness and ability to learn in the next unit.

This result obviously does not show that adaptive practice is a bad idea, or cannot be made to work well. It simply adds to the list of ideas that sound like they are more or less foolproof that turn out not to be: think spiral curriculum, or electronic textbooks. Thinking and learning is simply too complicated for us to confidently predict how a change in one variable will affect the entire cognitive and conative systems.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed